Caws Pobi

38.

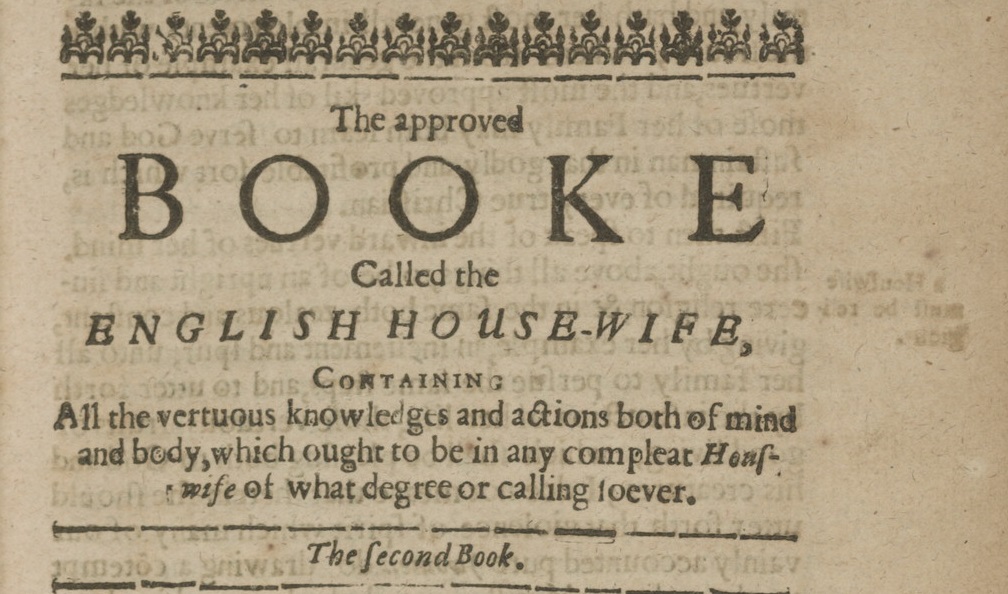

You can call it caws pobi, cause boby, or even Welsh rarebit or Welsh rabbit. It’s the same thing. It’s the food spoken of in 1542 by Andrew Boorde: “I am a Welshman, I do love cause boby, good roasted cheese.” (Fyrst Boke of the Introduction of Knowledge, 1542). There are earlier references to it, but by the 15th and 16th century it was essentially the Welsh national dish (First catch your peacock: The classic guide to Welsh food, B. Freeman, 1996, p. 31). It even shows up on a list of dishes presented in the late 15th century at Pembroke Castle by the Earl Marshal (likely Henry Tudor before becoming king):

Ballock broth, Caudle ferry, Lampreys en galentine, Oysters in civey, Eels in sorré, Baked Trout

Brawn with mustard, Numbles of a hart, Pigs y-farsed, Cockentryce

Goose in hogepotte Venison en frumenty, Hens in brewet, Squirrels roasted

Haggis of sheep, Pudding de capon-neck, Garbage, Trype de mouton, Blaundesorye, Caboges, Buttered worts

Apple muse, Gingerbread, Tart de fruit, Quinces in comfit

Essex cheese, Stilton cheese, Causs boby(Mediaeval Pageant, J.R. Reinhard, 1939, p. 42)[emphasis mine]

You must be logged in to post a comment.