This was my first time doing a poll to determine what I was going to make for Culinary Night. Candy won out over Andalusian bread. I’m thinking I may continue to have polls to determine what I’m making.

First off, this one isn’t my research or recipe, instead I’m basing it on the work of Jana of the Time Travel Kitchen. More specifically I’m taking this from the entry To make Penydes (I believe it’s pronounced pen-ids based on the Middle Eastern “panids” see here )

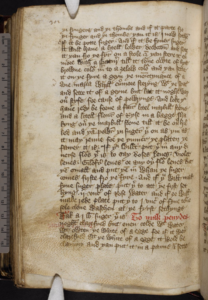

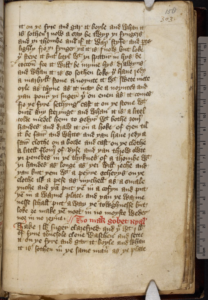

With that being said, this comes originally from Curye on Inglysch, specifically from Harley manuscript 2378. Here’s the original:

And the version in Curye on Inglysch:

To make penydes. Tak a lb. suger þat is noght clarefyed but euen colde wth water wythowten þe whyte of a egge for if it were clarefyed wyth þe white of a egg it would be clammy. And þan put it in a panne and sette it on þe fyre and gar it boyle, and whan it is sothen inow asay betwyx þi fyngers and þi thombe and if it wax styfe and perte lightly fro þi fynger þan it is enow: but loke þou stere it but lityl wyth þi spatur in hys decoccioun, for it will benyme hys drawyng. And whan it is so sothen loke þou haue redy a marbyll stone. Anoynte it wyth swetemete oyle as thyne as it may be anoynted and þan pour þi suger þeron euen as it comes fro þe fyre sethyng. Cast it on þe stone wythouten any sterynge, and whan it is a litel colde medel hem togedyr wyth bothe youre handes and draw it on a hoke of eren til it be faire and white. And þan haue redy a faire clothe on a borde, and cast on þe clothe a litell floure of ryse, and þan throw owte þi penydes in þe thyknes of a thombe with þi handes as longe as þei will reche, and þan kut þem wyth a pere scherys on þe clothe, ilk a pese as mychell as a smale ynche, and þan put þem in a cofyn and put þem in a warme place, and þan þe warmnesse schall put away away þe towghnesse: but loke ye mak þem noyt in no moyste weder nor in no reyne.

And here’s Jana’s version:

Penydes

4 C. sugar

3 T. vinegar

1 1/4 C. water

1/4 t. cream of tartar

1/2 C. white corn syrup

Please go see her site for much more information on it. But here’s an abbreviated version of her steps:

- Put ingredients in a pot on stove, heat slowly

- Bring to rolling boil, cover with lid for two minutes

- Remove lid, insert candy thermometer

- Bring up to correct temperature (300F)

- Pour onto buttered marble candy stone

- Spread and flip candy until cool enough to touch

- Add in flavour oil (about 1 tsp)

- Keep folding it in on itself until cooled enough to pick up

- Pull over buttered hook, and pull down a foot or two

- Loop and continue pulling it until it turns “opaque white”

- Return to stone and pull it into a rope

- Cut into pieced with buttered kitchen scissors

- Toss with rice flour or powdered sugar

I’ll be basing mine on Jana’s version while making a few changes.

Regarding the stage to cook it to. The recipe says “whan it is sothen inow asay betwyx þi fyngers and þi thombe and if it wax styfe and perte lightly fro þi fynger þan it is enow” and by later says “put þem in a warme place, and þan þe warmnesse schall put away away þe towghnesse”. I originally thought this meant the the firm-ball or hard-ball stage as that would be easily kept soft in a “warm place”, rather than Jana’s interpretation of it being the hard-crack stage. This is supported by Ivan Day in his essay “the Art of Confectionery” (pdf) where he says that boiling beyond 245°F (called the feathered stage in the 16th century or the firm ball stage modernly) was rare before the 19th century. After more work on this and trying the recipe for myself I’m not sure if Day is correct in that but it does seem to be in line with the 14th century recipe this is based on and is also in line with the Boston Cooking-School Cook Book’s (1896) recommendation (mentioned shortly). But there is that bit in the recipe “it wax styfe and perte lightly fro þi fynger” which translates to “it grows stiff and parts lightly from the finger” which makes me wonder if it might not be supposed to be at the soft crack stage, however the same wording could possibly be used to describe sugar at the blow stage (230-235°F just before it gets to soft ball) however I’m not sure if the method used after that (the pulling of it until it turns white and the forming into a thumb thick rope) would be possible at that stage as I’m still a novice at this. I’ll be doing this recipe near the top of the hard ball stage (265°F) but I intend to try it at both higher and lower stages in the future.

Jana uses vinegar, cream of tartar, and corn syrup to make the sugar boil easier. In The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (1896) the recommendation is 2 1/2 lb sugar, 1 1/2 cups hot water, and 1/4 tsp cream of tartar (p453) or 2lb sugar, 2 cups boiling water, 1/4 tsp cream of tartar (p457). As Jana mentions, the additions beyond water and sugar “make it a little bit easier to work with, and keep it from turning grainy and weird longer”. In the 19th century they used cream of tartar for the same thing (acid helps stop the formation of crystals). I will be using vinegar (apple cider vinegar as that’s what I have on hand).

I’ve mentioned the Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (1896) a few times and in it they mention two key ways to use boiled sugar. First to heat it to soft ball stage and then pour it onto your tile for cooling and kneading (to make “White Fondant” p453), or second to heat it to the hard crack stage then stop the heating by placing the pot into a larger pot of cold water, and then into a pot of warm to keep the sugar malleable, then drizzling the sugar over rods to turn it into strings of sugar (to make “Spun Sugar” p457). Although both sound interesting neither lines up properly with the penydes recipe.

I was originally planning to use cream of tartar as my acid (based on Boston Cookery-School). From what I can tell, and according to the OED, tartar shows up in medicinal books as early as the early 15th century “First I made hym ane emplastre of tartare of ale, i.[e]. dreggez.” (Arderne’s Surgery · 1425.) Clearly continuing in that vein into the 16th century: ” Wyne Lyes called Tartarum..menglid in oyle and Veniger is verye good.” (Pope John Xxi · The treasury of healthe conteynyng many profitable medycines (transl. Humphrey Llwyd) · 1st edition, 1550). Also, Alessio mentions how to properly prepare and refine cream of tartar (The secrets of the reverend Maister Alexis of Piemont 1565, p264). He also uses it in medicinal ways, to help with making brass, as a cleaning product, as part of making dyes, to help with gilting. However, none of them use it for culinary purposes. In fact candy recipes remain being just water and sugar (plus flavour and colour) at least until the 18th century from what I can tell. So I won’t be using tartar, but for my first attempt I will, as previously mentioned, use vinegar – again, this was not used in period.

Even a work as late as Queens Closet Opened (1655) only uses sugar and water or rose water. Note, this is in “A queens Delight: or, The Art of Preserving, Conserving, and Candying” not in the more popular “The Compleat Cook”:

To make Sugar of Wormwood, Mint, Aniseed, or any other of that kinde.

Take double refined Sugar, and do but wet it in fair water, or Rose water, and boyl it to a Candy when it is almost boyled take it off, and stir it till it be cold; then drop in three or four drops of the Oils of whatsoever you will make, and stir it well; then drop it on a board being before sifted with Sugar. (221)

Feel free to use either the original method or Jana’s method. I will be using Jana’s steps however.

So my recipe so far:

Penydes

- 1 lb sugar

- 1/4 cup water

- 1/4 cup apple cider vinegar

- flavour oil (cinnamon in this case)

- rice flour or powdered sugar

- Put ingredients in a pot on stove, heat slowly

- Bring to rolling boil, insert candy thermometer

- Bring up to correct temperature (265°F.)

- Pour onto buttered marble candy stone

- Spread and flip candy until cool enough to touch

- Add in flavour oil (about 1/4-1/2 tsp)

- Keep folding it in on itself until cooled enough to pick up

- Pull over buttered hook, and pull down a foot or two

- Loop and continue pulling it until it turns “opaque white”

- Return to stone and pull it into a rope

- Cut into pieced with buttered kitchen scissors or buttered knife

- Toss with rice flour or powdered sugar (I prefer powdered sugar, but the more period method is rice flour)

Amazingly it worked. The candy is hard at first but softens in the mouth, though not as much as I’d like, it still sticks to the teeth. I think I’m going to try having it at a lower heat next time, perhaps 235°F. I also intend to try one at the soft or hard crack stage.

- setting up my work space

- setting up my work space

- liquid’s been added to the sugar (and moved to a smaller pot)

- time to cook it

- getting there

- pouring out the candy

- beautiful sugar on my marble

- I use a 2’x1′ marble tile

- ok, no pictures of the actual pulling, sorry, but here’s the end result

- I made a bunch of different shapes to try different techniques

- I’m particularly proud of this one

- the scoring while malleable then breaking apart after cooling seemed the best method

- candy that was scored while malleable breaks apart easily

- lots of candy

If you want a different style, here’s a Portuguese version from A Treatise of Portuguese Cuisine from the 15th Century:

Taffy(?). Paste of sugar or syrup boiled to thick stage, from which various sweets are made Make a syrup with a kilogram of sugar and add a few drops of flower water. Leave the pot on the fire, until the syrup reaches the point of boiling. To recognize this point take a tiny bit and introduce it to cold water, then in the syrup, and again in the cold water. If the sugar pulls apart from the tiny bit, maintaining it’s cylindrical form, and crystalizes, the point will be good (reached). If that test proves difficult, put a little syrup in cold water, make with it a little ball and taste (test) it with your teeth. If it doesn’t stick, the point is reached. Take a slab of marble greased with oil of flowers or almonds, and pour the syrup over it quickly, for it not to get sugary (crystalize) and, very quickly, give it three or four turns with a spatula or wooden spoon. Next, with both hands, stretch the sugar as far as possible over the marble, making with it the motion of opening and closing your arms, very quickly. After it is well stretched, run your hand over the paste, in only one direction, and twist it a bit giving it the shape of a spiral. It is necessary to do all that outside the air flow (away from drafts), so the sugar doesn’t crystalize befor the operation is completed. Finally, spread a damp cloth over a table, and place over it the braid of sugar. As soon as it hardens, cut it into little pieces.

Fun fact, if the candy is at the soft crack stage it will stick to your teeth. So, they’re either heating them to hard crack or they want them only brought to the firm/hard ball stage. I suspect it’s the hard crack stage (regardless of modern sources claiming that they didn’t bring their sugar to that stage till a century later) as it’s much harder to return to an earlier stage, so the instructions are telling you how to tell once it’s passed soft crack, not that you don’t want to reach soft crack. With that in mind the next time I do this I’ll be going all the way to hard crack stage, as that seems to be used much earlier than some sources think.

3 Comments

Christa Bedwin · September 15, 2017 at 3:09 am

Wow! Great description! I feel that I was almost there to taste it. Thanks for the excellent blog post.

Victoria Vargo · June 15, 2021 at 3:36 pm

It’s not hard Crack stage. Everyone is interpreting this recipe wrong. Your range of boil is great! But “put away in a warm place and that will take away the toughness”.

That’s my interpretation and it’s because the candy will “turn or grain” into a candy that melts in the mouth, like an old fashioned buttermint candy. Add a tablespoon of butter, thank me later. Yummy! Lol

Tomas de Courcy · October 13, 2021 at 4:29 pm

I used hardball stage rather than hard crack and I find it works best there (though I’ve tried a few different temperatures), so I think you’re right. What temperature have you found it best at?

Comments are closed.